Weekly blogging hasn’t really worked. I was immersing myself in Melbourne life and didn’t really feel like writing it up at the time. The transitory space of the airplane seems to be the ideal time for this. I’m on the 14 hour non-stop flight to Johannesburg following one month in Melbourne. I’ve just had two days in Sydney, which mainly involved meandering about getting lost. I went to see Once in Royal David’s City by Michael Gow which was well worth it (funny, sad, clever, political). I popped my head into the Museum of Contemporary Art but it was all feeling very familiar (I think it was the same hang of the collection I saw when I was here in 2012). Anyway, the beach was calling. Bondi beach is a strange place full of fit people jogging with their iphones strapped to their arms, keeping out the sound of the sea and birds.

image: a view of Sydney

Post-conference, it took a while to get the balance right between productive sabbatical time and tourist-time. When seeing the sites, I felt like I should be working, and when working, I thought I should be out and about making the most of being somewhere different. The notion and experience of a sabbatical is quite unusual, it’s never happened to me before. It’s a strange limbo-like space where some well-needed thinking time starts to occur because there’s not a long list of things I should be doing. In my case, this has been a chance to further some of the research I’ve been doing into art and politics, but also to have valuable, slow conversations with some amazing people which has furthered my thinking and understanding (including Marnie Badham, Lachlan MacDowall, Rob Ball, Bianca Tainsh, Adva Weinstein, James Oliver, Bern Fitzgerald, Andy Best, Danielle Wyatt and many others). I got to spend some quality time with Anne Douglas, who was my PhD supervisor and who is also coincidentally in Melbourne on a fellowship. Anne gave an inspiring talk at the VCA last week on re-imagining the ‘social turn’, thinking beyond binary oppositions (e.g. control / freedom, autonomy / control) and towards contingency, situatedness and improvised aspects of leadership in the arts.

image: our flat on the VCA campus, next to the NGV

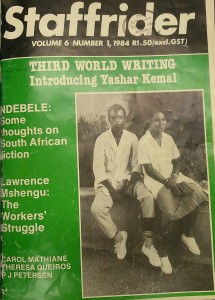

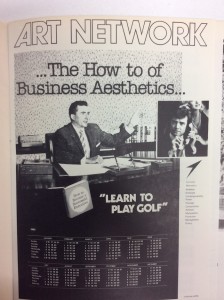

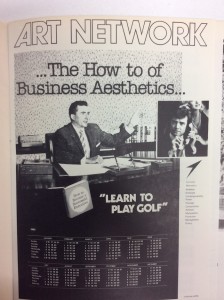

I haven’t done as much reading as I thought I would this month, but I spent some valuable time in the VCA library as part of my research into Australian community arts histories and started to read Gay Hawkins’ book ‘From Nimbin to Mardi Gras’ (1993) which is a fascinating insight into the policy-driven history of community arts. Hawkins critiques Left accounts of community arts as ‘romanticised’ and ‘stultifying’, too simplistic in their accounts of ‘ordinary people’ against the capitalist state. Instead, she focuses on the official invention of community arts and a framework of analysis based on the historical and institutional context of the development of a democratic cultural policy in Australia marked by the setting up of a separate Community Art Program in 1973. There are some interesting parallels with UK policy development in relation to community arts funding (e.g. the Arts Council of Great Britain established a Community Arts Committee in 1974). More on that in due course. A footnote in Hawkins’ book led me to an issue of ‘Art Network’ from 1982 which I dug out of the library, with a special supplement on ‘Socially Engaged and Community Art’. I was quite excited about this because it is a very early mention of the term ‘socially engaged art’. The earliest I have found in the UK is in Malcolm Dickson’s ‘Art with People’ published in 1995.

image: the subscription page from the Art Network magazine (1982)

My 1984 dinner in Melbourne took place on 3 March and was co-hosted by Bern Fitzgerald at Footscray Community Arts Centre and Marnie Badham, Centre for Creative Partnerships, VCA. Our guests were: Jon Hawkes, Heather Horrocks, Robin Laurie, Uncle Larry Walsh and Fotis Kapetopoulos. We held the dinner in the gallery space at Footscray, and ate a lot of Vietnamese food. The guests spoke of the relationship between art and politics at the time, including the fights against terms such as ‘community arts’ and ‘multiculturalism’, the importance of support and friendship between people, the rise and rise of bureaucracy and contradictions with indigenous ways of organising. I’m going to be setting up a website to house the research and audio of the dinners. Excitingly, it looks like there will be a dinner in Adelaide in June co-hosted by Steve Mayhew, who I met at the Spectres of Evaluation Masterclass and Marnie is looking to develop 1984 dinners on her travels to Indonesia, the US and Canada later this year.

image: the 1984 dinner at Footscray Community Art Centre, 3 March 2014

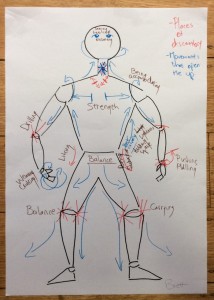

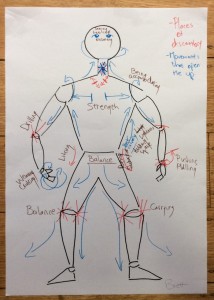

Other work-based activities in Melbourne these past few weeks have included a workshop I set up with Adva Weinstein, a performance artist and student I met during the Spectres of Evaluation Masterclass. We brought together five ‘cultural workers’ to map out and discuss physical and emotional relationships to work using drawing, discussion and movement. This is forming part of the Manual Labours practice-based research I’m doing with Jenny Richards and an article we are currently writing on the issues and implications of love and enjoyment of work. We did an exercise where we moulded our partners bodies into the shapes that we often find ourselves in to reflect on the physical and emotional experiences of these scenarios. My partner’s contorted, frantic pose, spitting swear words, perched on the edge of a chair reflecting me trying to answer a never ending flow of emails is an image I won’t forget!

image: one of the body drawings from the Manual Labours ‘Loving Work’ workshop

I also set up a workshop with Anne Douglas for PhD students at VCA about their practice-led research, asking the question: How is my Art Research? How is my Research Art? Everyone was invited to bring an ‘object’ of their research and we worked in pairs to interview each other, using the object as a talking point. This was a difficult exercise, but really pushed us to reflect on the specifics of the practice and how it related to the research questions we have (acknowledging that the questions can arise from the practice rather than a specific research question always directing the practice from the outset).

image: the collection of ‘objects’ brought to the practice-led research workshop at VCA

Other things we did: Rob Ball took Barry and I on a very enjoyable ‘Artist Run Initiatives’ (ARI) tour on Melbourne bikes, during which we made up a term for a new genre, Flop and Prop, for all the various found materials we found resting carefully against gallery walls. ARI’s are a peculiarly Australian phenomenon which seem to involve artists paying to use galleries as a career step towards commercial representation or shows in public spaces. I need to find out more as this seems an odd set up, especially in relation to campaigns elsewhere for fair pay for artists/cultural workers.

Andy Best took us to Heide Museum of Modern Art, an amazing art gallery just out of town, where artists John and Sunday Reed lived from the 1930s-80s. We saw Future Primitive, an exhibition of contemporary Australian artists, and the beautiful modernist extension built for the couple to live in.

image: me in a pond in Tasmania

Barry and I also spent three nights in Tasmania, driving around the beautiful countryside, walking up a couple of hills, drinking wine, meeting distant relatives (the lovely Dillon’s on my mum’s side), visiting the old convict colony on Port Arthur and spending a long time in the Museum of New and Old Art (MONA needs a whole blog post but I’m not sure I can be bothered).

image: a page from a 1984 Time Magazine bought in an Op Shop on the Great Ocean Road

Barry, Anne and I borrowed Hazel, Marnie’s car, to drive up the Great Ocean Road and stayed in vidmate an amazing airbnb house in Port Campbell, just past the Twelve Apostles. After some stunning views, winding roads, lovely grub and a speeding ticket (I discovered later), we managed to get back to Melbourne just in time for a mini-gathering at our flat before experiencing Melbourne’s White Night – a festival in the CBD that runs from 7am-7pm with events, light projections, outdoor exhibitions. The streets were packed, people were clambering up the sides of one building trying to take a peek at the synchronised swimming because of the two hour queue to get in. The crowds were eagerly searching for a cultural experience, hungry for the spectacle, happy to be part of it. It seemed we were taking to the streets for the sake of it, no one quite sure of the destination or purpose. We lasted until about 2am and went to bed after watching a Pierre Huyghe film in the park opposite our flat.

<a href="http://sophiehope prix de viagra.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/ML_lovingwork.jpg”>

image: drawing on the body, Loving Work workshop, VCA

Another thing that has stuck in my mind is the aboriginal tour Anne and I tagged along to that was organised for some VCA students. It started opposite the Crown Hotel, under the train bridge, where some of Melbourne’s homeless gather and where homeless man Wayne ‘Mousey’ Perry was murdered in January this year. Our guide, Dean Stewart (a Wemba Wergaia man), set out to challenge our perceptions of the city, and he successfully achieved this in my case. We went a short distance along the Birrarung river (original name for the Warra) in two hours but covered hundreds of years of history, focusing on the changing landscape we were walking through. The city of Melbourne was developed rapidly. Within 25 years of the invasion by the English in 1835 and development of the gold mining industry, the landscape had changed dramatically from eucalyptus forests and wetlands to a built up city. Dean described it as a cultural tsunami; about 80% of the indigenous population were wiped out. This meant that important oral histories and traditions were lost (such as the name, songs and dances connected to the waterfall that marked an important crossing and fresh water site before the English invasion).

The tidy patch of imported East African grass we walked across was wetland less than 200 years ago. Dean points out that it was a place the Wurundjeri, the traditional owners of the land where Melbourne was built, used to eat, drink, meet – a custom that still attracts people to the bars and restaurants of the Southbank today (at least those who can afford it). While Dean was keen for the purpose of the tour to be for anyone born in Melbourne to reconnect to their roots, the important process of understanding cultural and social histories of relationship to place was compelling and thought provoking. It left me with the obvious shame of being connected to English history (I’m feeling that a lot on this trip), but also a question of how and why we connect to layers of experience in the places we come from, walk through and inhabit, in a way that might inform and complicate attempts to preserve and to change. This seems to be about a slow, careful and respectful listening to those around us and the places we walk through.