Still from the The Truman Show (1998)

I’m heading to a seminar in Zagreb this week called The Age of Cultural Participation: Democratic Roles and Consequences and wanted to prep some thoughts before I go.

The panel discussion I’m taking part in is titled: Limitations and Perspectives of Participation – From Dark Side to Ideal of Participatory Practices and the other contributors will be: Nico Carpentier, Goran Sergej Pristaš and Nora Sternfeld.

I am drawing on old PhD research, some more recent interviews and some literature I’ve been revisiting and rediscovering:

Bill Cooke and Uma Kothari’s edited book Participation: The New Tyranny (2001)

Erving Goffman’s The Presentation of the Self (1959)

Barbara Cruikshank’s The Will to Empower (1999)

Francois Matarasso’s A Restless Art (2019)

Scott Rankin on cultural justice (2018)

Steve Rolf on governance and governmentality in community participation (2018)

My entry point for thinking about participation is the socially engaged art commission and I’m using this to explore the meanings, politics and economics of participation. Here are some points I made in my PhD (2011). I’m obviously very cynical about the socially engaged art industry here!

- Increasing opportunities for socially engaged art commissions over the last ten years have led to a professionalisation of the field and with it a focus on the artist as entrepreneur who can charge for their empowering services. Paradoxically, this has hindered the power that participants can have in terms of deciding their own modes of practice, despite the premise of the projects being based on participation and social engagement.

- It is assumed that the professional, trained artist can bring a conceptual approach and high-quality experience of art to a culturally barren landscape of deprivation that did not realise what it was missing. The local populace pay inadvertently through taxes and lottery tickets for a service they never asked for or may never use.

- Why is it that artists are parachuted in as catalysts, researchers or irritants when they rarely have the time, inclination or funds to do this in the neighbourhoods where they live?

- If the ‘empowerment industry’ is constructed to provide professionals with incomes, to what extent does it rely on perpetuating systems of exclusion and illusions of social inclusion in order to keep the industry afloat and the professionals in work?

Ouch.

Participation as performance

Let’s take this participatory art commissioning industry as the stage, participants as performers and the commissioned artist(s) as the director(s) and curators as stage managers. How can we use this metaphor to understand better what participation is and what happens when we get messed up in it, adopt the lingo and accidentally or on purpose find ourselves participating, or not-participating? Who is able to perform? Who sets the stage? Who writes this script?

Participation implies a web of power relations: “acts and processes of participation… can both conceal and reinforce oppressions and injustices in their various manifestations…” (Cook and Kothari, 2001, p.13).

Participation = an invitation into something already (partially) formed?

Participation = an enforced, embarrassing encounter?

Participation = the existing and evolving power-relations between people, things, contexts, environments?

Like Kothari (in her article in the above publication), I’m taking Foucault’s approach to understanding power-relations as weaving in and amongst us, at all times, including through acts of participation: “an individual’s behaviour, actions and perceptions are all shaped by the power embedded and embodied in society” (Kothari, 2001, p.144). The word participation is loaded with unspoken assumptions. Cooke and Kothari ask, “What is the politics of the discourse of participation?” (p. 7).

Why is participation (in the context socially engaged / participatory art) considered a good thing to do? Why is it considered better than not-participating? I have found that the motivation to make connections, get involved and create a sense of community identity can often be met with an unwillingness to participate on the terms and conditions set by the artist or commissioner.

Why are we always trying to get other people to participate in things? How do these invitations to participate veil other political motives, such as transferring responsibility from the state to the individual through forms of governmentality (see Rolf, 2018): “Whilst governance implies a process of the state ‘stepping back’, governmentality suggests that such an ostensible withdrawal may conceal a degree of ‘stepping into’ society in order to control behaviour and surreptitiously responsibilise citizens.”(Rolf, 2018, p.581). Participation could be understood as a ‘technology of citizenship’, as a system for turning individual subjects into (self) governable citizens (Cruikshank, 1999). If these ideas/ideals underpin attempts to get people to participate, what are the issues with this? What/whose ideologies are we perpetuating when we embrace the language and practices of participation? What are the ethics and politics of this?

In the projects I have been involved in there is often an underlying premise to encouraging participation: that people need help in order to help themselves. By participating in this, you will be a) happier b) healthier c) more employable d)distracted from the defunding of public services e) less of a burden on the state f) more connected to your neighbours g) ideally all of the above. This is also class-based. Are the middle classes expected to participate and communicate with each other and create a sense of community or is it accepted that the middle classes are defined by their empowered [entitled] sense of independence and privacy?

Acts of non-participation

I think deciding not to participate or participate in ways that contradicts expectations of participation is under-explored. Here are a couple of quotes from some residents who did not want to get involved in an art project happening in their neighbourhood:

“Everyone’s kind of in their own little circle, they’ve got friends, they’ve got family. This might sound really anti-social but do I really want to meet other people? I’ve got enough friends”

“I’m not a person that would be involved in any community event anyway. I find it hard to believe it will work without pushing people to do it, offering a big incentive”

In another project, non-participation is driven by anger at not being involved enough in the process:

“They’re not listening. They’ve got their agenda, from day one. We know what you want, we’re not going to do it anyway… they’d already decided”

“If you can’t do what we ask, then bugger off.

Acts of non-participation are often seen as a problem with the individual or characteristic of the area, rather than a critical reflection on the project itself. One of the artists for example, was ‘genuinely surprised at how many people have not participated, out of all the contacts and places she visited. But this in itself is part of the place – reflecting people’s values and attitudes”.

People have learnt to rely on or ignore participatory activities in their neighbourhoods as something they have a right and reason to engage in or that they find irrelevant to their cultural needs. One can take or leave these extra-curricular activities in one’s life depending on time, information, resources and interest.

The projects I was researching as part of my PhD revealed that it is often when the limits of a project are sensed that a critical awareness of the conditions of the invitation to participate come into focus and one is able to reconsider one’s relationship to it. The stage, props, performance are revealed (it’s the Truman Show moment). Often, one only discovers these limits when they pose a barrier or obstacle to the progression of the project.

Methods for keeping things messy?

In my PhD I was researching the contradictions in frameworks for participation constructed by artists, curators, commissioners and/or funders, which are open to others to participate in the ‘wrong’ way so as to change, contest and critique the direction, parameters and ideologies of that framework. I keep trying to find ways to point these out by developing mechanisms for embracing and encouraging these encounters within the frameworks of the commissioning process. These methods include playing a card game (Cards on the Table, developed with Ania Bas, Sian Hunter-Dodsworth, Sophie Mallet and Henry Mulhall – more info to come!) to reflect on the language used in project meetings, the assumptions behind each other’s roles and agendas; writing lengthy timelines of projects together to listen to each other’s diverse beginnings, middles, ends of the life of a project, what sticks, what’s forgotten (Social Art Map); anonymising stories of failure so as to unpack performances of success (Performative Interviews) and facilitating groups of expert/serial participants to critically evaluate the meanings, methods, experiences of participatory art (Critical Friends).

Still from a Performative Interview (2007)

These are experimental methods in opening up the process of reflecting on participation from the perspective of participants in the process. They result in complex, messy power-maps and timelines indicating who is who, the strains, tensions, push and pull of agendas and identities.

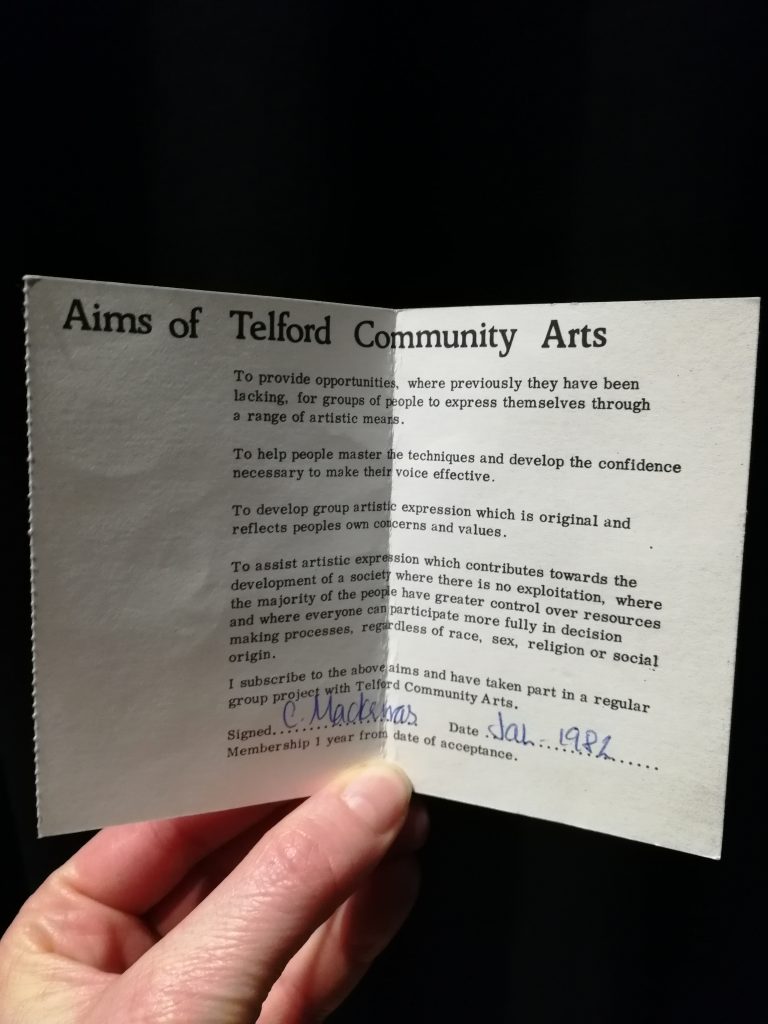

Exit stage right: Cultural democracy as a different way of performing?

I have been looking for moments of cultural democracy that weave their way uncomfortably through the prescribed frameworks of imposed art-as-service contracts in a way that exposes the structures and frameworks of these contracts. There are numerous ways and means for people to participate in culture and society depending on time, budgets and motivations. The assumption that one form of culture or a certain mode of engagement is more worthy and important than the next is patronising to say the least. Cultural democracy challenges discourses of participation as there is nothing to participate ‘in’, we just do stuff from the position we are standing.

All this raises questions about the positions we stand from, how do we decide what to do with our (limited) time and resources? Where to put our energies? What will the implications be of deciding to participate in this and not that?

Anyway, I’m slowly merging from maternity leave and this is a way for me to start ‘participating’ in non-baby-related discussions (which I love as well by the way and will no doubt find a way of weaving in!). Looking forward to thinking this through with colleagues later this week!